On Being Too Attached to One's Babies.....

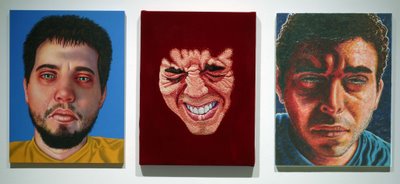

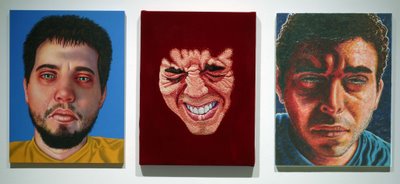

So I just brought back 3 Crying Men paintings

from Miami, having picked them up from Chelsea Galleria so that they can go to an upcoming show... (they will go back to Chelsea, along with NEW Crying Men, during Art Basel). I was itching to get home, so that I might hang them up in my studio and finally get another good look at them. They went directly to the Frost Museum show last summer, then to Chelsea, and I have not seen them since. So here's the thing: I realize that I am happier to have them back than I would be if they all sold and I got a check. As I mentioned a few days ago, I have recently dropped off a landscape to the gallery that I might never see again. This is distressing, and a part of this new deal that I had not bargained for.

from Miami, having picked them up from Chelsea Galleria so that they can go to an upcoming show... (they will go back to Chelsea, along with NEW Crying Men, during Art Basel). I was itching to get home, so that I might hang them up in my studio and finally get another good look at them. They went directly to the Frost Museum show last summer, then to Chelsea, and I have not seen them since. So here's the thing: I realize that I am happier to have them back than I would be if they all sold and I got a check. As I mentioned a few days ago, I have recently dropped off a landscape to the gallery that I might never see again. This is distressing, and a part of this new deal that I had not bargained for.

Up until recently, when I was still single, I would bring whatever painting I was working on into my bedroom each evening: I would look at it for a while while falling asleep, then look at it again with fresh eyes in the morning before getting up. It would allow me to see things that might not work, see it wih fresh eyes in a new space, etc. I always work on a painting until there was not one possible thing that I could do to it to make it stronger. Towards the end, I would sit in front of it for a long period of time and make a list of all the things that needed to happen to it before it was done, and cross them off one by one. Then I would declare it finished, and I would hang it on a prominent wall in my home or studio, someplace where I would be sure to see it every day. I would look at it some more. There was, on average, one more hour's work that went into each of these paintings before I released them into the world.

SaraP wrote in a comment to an earlier blog:

"On a somewhat related note - six years ago my mentor was dropping off a year's worth of work to her NYC gallery (this was comprised of 5 highly-detailed, 3-by-5 foot architectural paintings of NYC scenes with slightly built-out relief surfaces of only about 2 inches deep). She had unloaded 4 from her car and a man standing in the gallery purchased them on the spot. She panicked and told the gallery director that was all the work she had...so she could keep the last piece that was still packed in her car (this painting still hangs in her house). The real bummer, so to speak, was that the guy lived out of the state so there was no gallery show for her that year. Clearly the work sold ($20K plus for her) but there was no glory in the end - so perhaps the opportunity to exhibit is as much a part of the art, too?"

This is the art world dream, right? Haven't we all heard the stories about artists who are so "hot" that there is a waiting list for their work? How are those artists different from someone knitting sweaters as fast as they can to sell them? The above story is my idea of a nightmare. It clearly spells out to me what I want and don't want for my own work. I think, if it were up to me, I would sell my work only to museums, or only after 5 years had past, and it had experienced an active exhibition life. Not only would I be less attached to it, but people would have had the opportunity to see the work, write about it, etc., and I could go see it when it was being exhibited in the various venues. I learn from my own work: I try to do something new in each painting that I have never done before. How can I absorb the lesson if I never see the work again once it leaves the easel?

When you work on a painting for 6 months or a year, the details of every millimeter of the canvas are burned into your brain. You remember painting the stitches of the sweater, the highlights on the stitches, glazing the rows between the stitches, then the shadows that cause these loops to look like they go UNDER those loops. My paintings are not infatuations, but full blown, long-term love affairs. When you work on a painting for that long, the meaning often changes during the course of the process. "Fate of A Technicolor Romantic" started off as a painting about class and shame: an easily dismissed white trash living room, full of films and books to make the viewer take pause in making judgments. It developed into a self-portrait of my core values, then a war of light between the idealism of the blue TV light and the reality of a dim 40-watt light bulb. This painting has strong ties to my family: I remember sobbing in front of this painting more than once while working on it, partially because it was succeeding in doing what I wanted it to do, and partly because it was so successful it brought me back to places I didn't really want to be. I was doing two weeks of all nighters to finish another painting for a show in 1996, and my sleep-deprived brain had the strong desire to lick the surface, because I was so happy with the texture. On another 2 a.m. final-crunch occasion, I cried with joy when I realized that The Defense Mechanism Coat, my first 3D object, went from a conceptual sketch to a 150 lb. real thing, and it was actually going to work, not fall apart the minute I hung it up.

To use a common but inauthentic (I have never given birth to a PERSON) metaphor, I devote myself to the creation of a piece, think about it as I am falling asleep every night and waiting in line at the supermarket, and usually have a lengthy, painful, exhausting finish that feels like I have taken years off my life. Then, when I go to see it hanging in the gallery, I can't believe I made that thing hanging on the wall, and I forget the pain.

In undergraduate school, it was vulgar to talk about selling one's work. You made the strongest work possible, and no one ever talked about what was supposed to happen after that. Today it seems (maybe I am wrong) that most artists want to be famous, and to sell lots of work for lots of money. What is the point? The artists often don't know who purchased their work, because everything is handled by the dealer, and they like it that way. What if a complete as*hole who likes the work for all the wrong reasons wants to buy an important piece that you devoted half a year of your life to? The thought is disgusting, vulgar, and not too far away from selling your body.

So I just brought back 3 Crying Men paintings

from Miami, having picked them up from Chelsea Galleria so that they can go to an upcoming show... (they will go back to Chelsea, along with NEW Crying Men, during Art Basel). I was itching to get home, so that I might hang them up in my studio and finally get another good look at them. They went directly to the Frost Museum show last summer, then to Chelsea, and I have not seen them since. So here's the thing: I realize that I am happier to have them back than I would be if they all sold and I got a check. As I mentioned a few days ago, I have recently dropped off a landscape to the gallery that I might never see again. This is distressing, and a part of this new deal that I had not bargained for.

from Miami, having picked them up from Chelsea Galleria so that they can go to an upcoming show... (they will go back to Chelsea, along with NEW Crying Men, during Art Basel). I was itching to get home, so that I might hang them up in my studio and finally get another good look at them. They went directly to the Frost Museum show last summer, then to Chelsea, and I have not seen them since. So here's the thing: I realize that I am happier to have them back than I would be if they all sold and I got a check. As I mentioned a few days ago, I have recently dropped off a landscape to the gallery that I might never see again. This is distressing, and a part of this new deal that I had not bargained for.Up until recently, when I was still single, I would bring whatever painting I was working on into my bedroom each evening: I would look at it for a while while falling asleep, then look at it again with fresh eyes in the morning before getting up. It would allow me to see things that might not work, see it wih fresh eyes in a new space, etc. I always work on a painting until there was not one possible thing that I could do to it to make it stronger. Towards the end, I would sit in front of it for a long period of time and make a list of all the things that needed to happen to it before it was done, and cross them off one by one. Then I would declare it finished, and I would hang it on a prominent wall in my home or studio, someplace where I would be sure to see it every day. I would look at it some more. There was, on average, one more hour's work that went into each of these paintings before I released them into the world.

SaraP wrote in a comment to an earlier blog:

"On a somewhat related note - six years ago my mentor was dropping off a year's worth of work to her NYC gallery (this was comprised of 5 highly-detailed, 3-by-5 foot architectural paintings of NYC scenes with slightly built-out relief surfaces of only about 2 inches deep). She had unloaded 4 from her car and a man standing in the gallery purchased them on the spot. She panicked and told the gallery director that was all the work she had...so she could keep the last piece that was still packed in her car (this painting still hangs in her house). The real bummer, so to speak, was that the guy lived out of the state so there was no gallery show for her that year. Clearly the work sold ($20K plus for her) but there was no glory in the end - so perhaps the opportunity to exhibit is as much a part of the art, too?"

This is the art world dream, right? Haven't we all heard the stories about artists who are so "hot" that there is a waiting list for their work? How are those artists different from someone knitting sweaters as fast as they can to sell them? The above story is my idea of a nightmare. It clearly spells out to me what I want and don't want for my own work. I think, if it were up to me, I would sell my work only to museums, or only after 5 years had past, and it had experienced an active exhibition life. Not only would I be less attached to it, but people would have had the opportunity to see the work, write about it, etc., and I could go see it when it was being exhibited in the various venues. I learn from my own work: I try to do something new in each painting that I have never done before. How can I absorb the lesson if I never see the work again once it leaves the easel?

When you work on a painting for 6 months or a year, the details of every millimeter of the canvas are burned into your brain. You remember painting the stitches of the sweater, the highlights on the stitches, glazing the rows between the stitches, then the shadows that cause these loops to look like they go UNDER those loops. My paintings are not infatuations, but full blown, long-term love affairs. When you work on a painting for that long, the meaning often changes during the course of the process. "Fate of A Technicolor Romantic" started off as a painting about class and shame: an easily dismissed white trash living room, full of films and books to make the viewer take pause in making judgments. It developed into a self-portrait of my core values, then a war of light between the idealism of the blue TV light and the reality of a dim 40-watt light bulb. This painting has strong ties to my family: I remember sobbing in front of this painting more than once while working on it, partially because it was succeeding in doing what I wanted it to do, and partly because it was so successful it brought me back to places I didn't really want to be. I was doing two weeks of all nighters to finish another painting for a show in 1996, and my sleep-deprived brain had the strong desire to lick the surface, because I was so happy with the texture. On another 2 a.m. final-crunch occasion, I cried with joy when I realized that The Defense Mechanism Coat, my first 3D object, went from a conceptual sketch to a 150 lb. real thing, and it was actually going to work, not fall apart the minute I hung it up.

To use a common but inauthentic (I have never given birth to a PERSON) metaphor, I devote myself to the creation of a piece, think about it as I am falling asleep every night and waiting in line at the supermarket, and usually have a lengthy, painful, exhausting finish that feels like I have taken years off my life. Then, when I go to see it hanging in the gallery, I can't believe I made that thing hanging on the wall, and I forget the pain.

In undergraduate school, it was vulgar to talk about selling one's work. You made the strongest work possible, and no one ever talked about what was supposed to happen after that. Today it seems (maybe I am wrong) that most artists want to be famous, and to sell lots of work for lots of money. What is the point? The artists often don't know who purchased their work, because everything is handled by the dealer, and they like it that way. What if a complete as*hole who likes the work for all the wrong reasons wants to buy an important piece that you devoted half a year of your life to? The thought is disgusting, vulgar, and not too far away from selling your body.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home